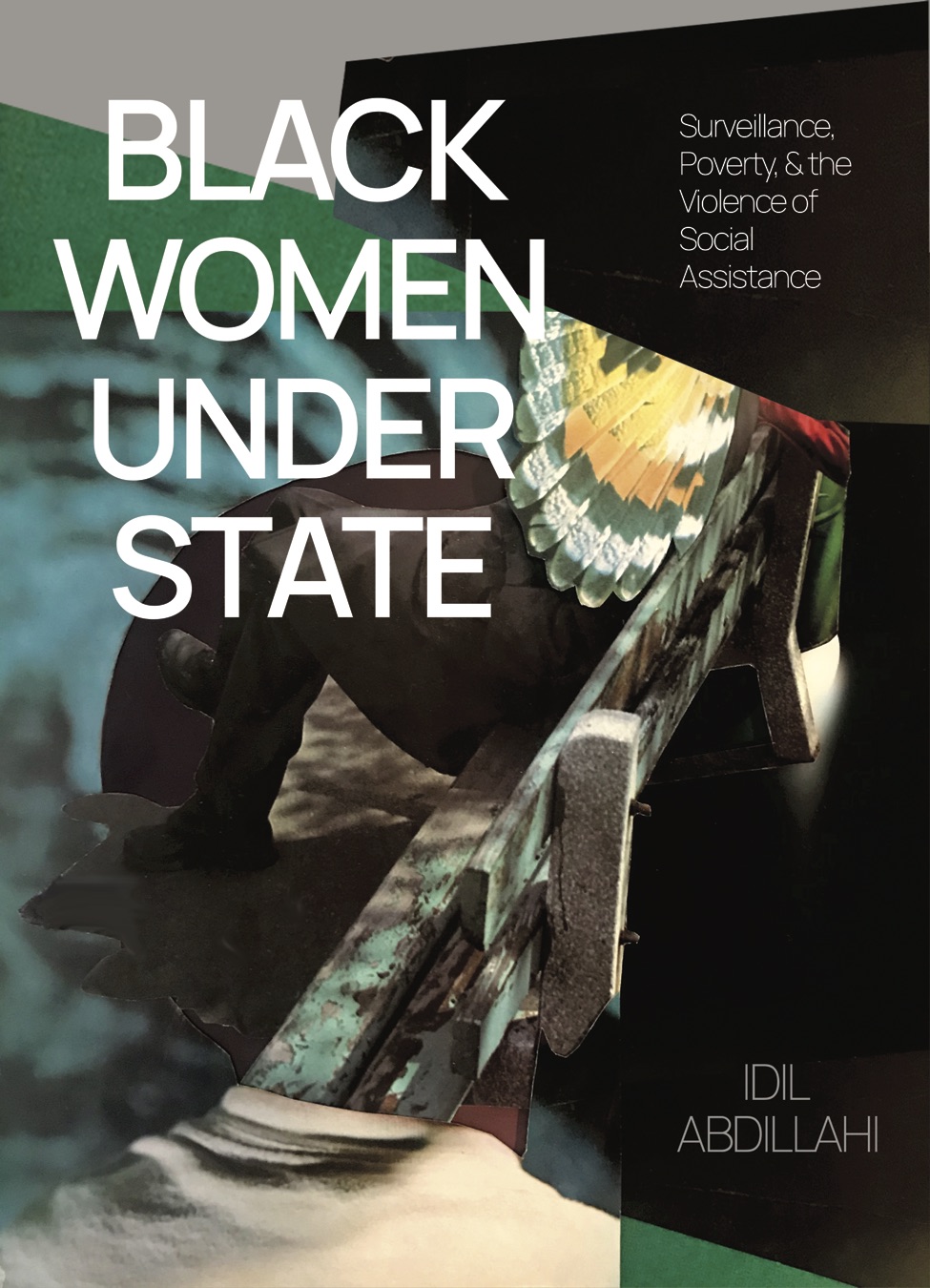

The lives and conditions of Black women are inseparable from, and inextricably linked to, all dimensions of social and political life. Black Women Under State centres on the realities of Black women, both in-process and theory, who are living at the intersections of race, poverty, surveillance, and social services. Abdillahi, who is uniquely positioned as a community organizer, practitioner, public intellectual, and scholar, engaged twenty women living at these life intersections in the greater Toronto area.

The text undertakes a deep and studied inquiry into these women’s subjective experiences of surveillance while on the province of Ontario’s social assistance program Ontario Works and interrogates the dimensional effects of those experiences. Offering a timely and crucial contribution to the discourse around abolition, Abdillahi makes explicit the ways in which social systems are made opaque so that we don’t connect them to the carceral state; this concept of carceral care talks to abolition as the broad concept that it is a fully-embraced understanding that abolition dismantles systems of policing that extend beyond the institution we call the police.

Three major themes emerge through her inquiry: surveillance, poverty, and morality each interconnected to a larger social and public policy discourse. Abdillahi employs Critical Race Theory and Black Feminist Thought as primary theoretical lenses as she animates the lives of these women, alongside and in conversation with existing research, theory and practice, revealing direct links among their experience, in order to demonstrate the shared, longstanding, and ongoing historicity of the interconnectedness of Black women’s experience globally.

The vast majority of the book’s citations are from Black Canadians, giving the text its own narrative around citational practice. Through a dynamic interlacing of contemporary critical thought and lived experience, Black Women Under State contributes to filling a gap in social policy literature, which has typically disregarded the subjective experiences of Black women or treated them as a mere addendum.

OUR BOOKS

OUR BOOKS

US Shopping Link (Buy the Paperback @ AK Press)

US Shopping Link (Buy the Paperback @ AK Press)